In 1950, poet Octavio Paz -- the only Mexican to have ever won the Nobel Prize for literature -- published El laberinto de la solead (The Labyrinth of Solitude). An essay about Mexican identity, nearly 60 years later it is still his most celebrated work. Some of it may be a little dated, but several of its chapters are startling in how relevant they still are.

The most pertintent and germane chapters are called "Mexican Masks" and "The Sons of La Malinche." Read together, they reflect that Mexicans typically hide behind impersonations -- metaphorical masks -- of servility or dominance, indifference or remoteness, disguising what are deep-seated feelings of suspicion, mistrust, resentment and inferiority.

At all costs, wrote Paz, Mexicans resist revealing themselves to others. Doing so would be a sign of weakness, and expose them to all sorts of terrifying vulnerability. Paz wrote that Mexicans viewed life as combat.

"His face is a mask," wrote the poet, "and so is his smile. In his harsh solitude, which is both barbed and courteous, everything serves him as a defense: silence and words, politeness and disdain, irony and resignation."

And, "He builds a wall of remoteness between reality and himself, a wall that is no less impenetrable for being invisible."

Perhaps Paz's essay goes some way in explaining why Mexican health care authorities, even with the CDC and the WHO breathing down their necks, have managed to avoid exposing details of how they managed -- or perhaps mismanaged -- the swine flu crisis. We stll know very little about why most of the few people who died of it are Mexicans, and next to nothing about the Mexicans who died. This article which appeared late last week reveals a few details.

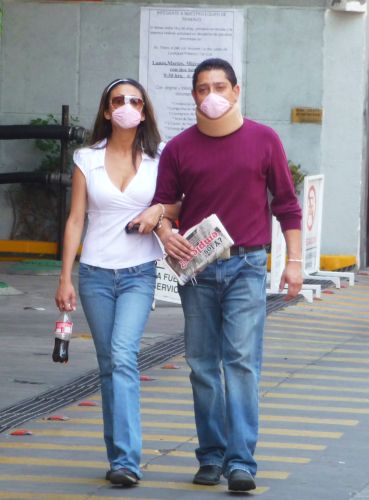

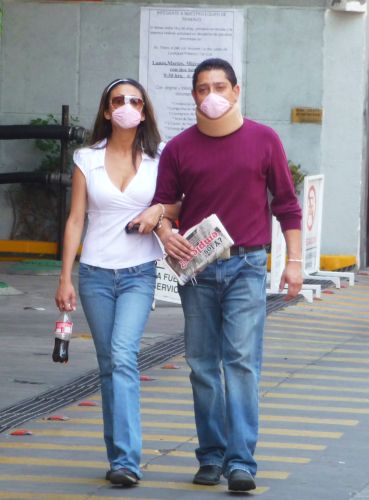

I wonder what the poet would have thought of those days when so many in Mexico City wandered its streets wearing officially sanctioned surgical masks, disguising (or perhaps exposing) whoever it is that they are. Perhaps he would have seen it as their shining hour. This montage is in his memory.

P.S. Here is a link to a story about a poor creature who must know how the Mexicans feel these days.