I took this flight not long ago between Houston and Mexico City. For a moment there, I thought I might end up in the Chekck Republic.

I took this flight not long ago between Houston and Mexico City. For a moment there, I thought I might end up in the Chekck Republic.

Mexico City

Gentrification?

The Colonia Tabacalera, near the centro histórico, has been down at the heels for a long time. This is a situation that might change, sooner or later. In 2010, for the bicentennial of Mexico's revolution, Mayor Marcelo Ebrard renovated the neighborhood's centerpiece, the Monumento a la Revolución and its surrounding plaza. The monument is a crypt for some of Mexico's revolutionary heroes, whose exploits are outlined in a museum in the building's basement. You can take an elevator and stairs to the top and get a view of the surrounding area. Or just stroll around -- on weekends families make the plaza their playground, and once in a while there is a free concert in the open air.

Still, the rest of the neighborhood has some catching up to do. The Frontón México, where jai alai had been played since the 1930s, has been closed since 1992.

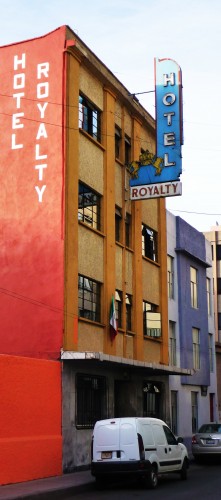

I sometimes fantasize about buying a building here and renting the apartments to my friends, which in practical terms is probably a recipe for disaster. The neighborhood is home to many short-time hotels with a deliciously seedy appearance. Still, I noticed that since the plaza was spruced up, some of these places, like the Royalty here, sprang for a new coat of paint on their facades.

Will any of them reemerge as the next hip boutique hotel?

While we are waiting for Philippe Starck, my friend Fabiola opened the Hostel Suites D.F. on calle Jesus Terán #38, a cute place with about 18 rooms, including dorms, family rooms and private rooms. Like most hostels, it's basic, but a cheerful place, and it's hard to beat the prices -- between 180 and 500 pesos, internet and breakfast included.

Grand Hotel

A long time ago, I wrote about Tania Negrete, who was the author of several articles about hoteles de paso. These are lodgings that rent their rooms on a short-time basis -- to people who are cheating on their spouses, people who live with their families (and as such have no place else to go), and couples who are looking to spice up their sex lives in one way or another. They are also mainstays for prostitutes who consider it unsafe to visit clients in their homes.

A long time ago, I wrote about Tania Negrete, who was the author of several articles about hoteles de paso. These are lodgings that rent their rooms on a short-time basis -- to people who are cheating on their spouses, people who live with their families (and as such have no place else to go), and couples who are looking to spice up their sex lives in one way or another. They are also mainstays for prostitutes who consider it unsafe to visit clients in their homes.

Hoteles de paso are all over Mexico City, and after you have lived here a while, they tend to go unnoticed, blending into the urban landscape. The anonymous character feeds into their general air of discretion -- they are not the sort of places whose clients want to be recognized walking in or out the front door (indeed, most have garage entrances so you can avoid the front steps).

Discretion above all was at least what I thought these places wanted to offer. Until a few months ago, when a friend invited me to the opening night party of N.Y.T. Roma, which may be the first boutique hotel de paso in Mexico City. Its name stands for New York - Tokyo - Roma -- not the city of Rome, but Calle Roma #40 in the Colonia Juárez, where it is located. How do you like this for an understated entryway?

Far from discreet, the owners of the hotel went out of their way to promote extravagance. At the opening, drinks and hors d'oeuvres were served on the terrace and the facilities were open for all to observe.

There are all sorts of hoteles de paso out there -- from the bargain basement, with saggy mattresses and cracked mirrors, where you don't want to look too closely at the sheets, to the deluxe, with round beds, mirrored ceilings and Jacuzzis in each room. Most tend to be clean, but generic in decoration. N.Y.T. Roma tries very hard to be extravagant, if not precisely stylish.

I liked the detail of the exposed showers next to the beds. The least expensive room at the N.Y.T. Roma runs at about $100 U.S. As most hoteles de paso are considerably more economical, I thought that if I stayed there I wouldn't want to vacate the premises after a couple of hours -- I'd want to stay overnight and get my money's worth. Still, I wondered if, um, noisy neighbors might make sleeping there a problem.

Gourmet comida corrida

A while back I posted aboutthe joys of the local fonda that serves a forty-peso comida corrida around the corner from my apartment. While I eat there fairly frequently, the truth about most fondas is that their comidas corridas tend to be heavy on carbohydrates and, depending on what you order for your main course, often on the greasy side.

On Calle Parras between Avenida Nuevo León and Avenida Amsterdam in the Colonia Condesa, however, there are two sidewalk fondas that serve what I have come to think of as gourmet comida corrida. They are not as cheap as ordinary fondas but, at eighty-five or ninety pesos, they are nevertheless a bargain, especially considering the quality of their ingredients.

At both the Gastrofonda Quim Jardi -- named after its chef, who is either a Mexican Catalan or a Catalan Mexican, depending on your point of view -- and the fonda Kousmine next door, run by a Frenchman who posts certificates with his culinary credentials on the outside tarp, you can get meals that are easier on the belly and the blood sugar than at ordinary fondas.

The first course are soups that tend to be made with fresh herbs and vegetables, and the second course -- instead of the rice or soggy spaghetti served at ordinary fondas -- is salad made with fresh dressings. For the main courses, at each place, you have your choice of chicken, beef, fish or something vegetarian, again, all prepared with fresh ingredients and sometimes extraordinary sauces. Quim, for instance, has a fish in a delectably spice mole, while the Frenchman makes a lovely arrachera with soy sauce and crunchy vegetables. Desserts are homemade and served with bracing espresso.

Menu at Kousmine. Lady, would you please get your head out of the way?

No coffee in Cuautitlán

Not long ago, they began commuter train service from downtown to the northern outskirts, a place called Cuautitlán Izcallí that is actually situated in Mexico State but considered part of the urban sprawl of Mexico City. Although it's a ride of only a little more than twenty miles, traffic tends to be so bad that it can easily take you two hours or more to get there or back in a car. I had only been to Cuautitlán once, a few years ago, and the ride home in a taxi was so excruciatingly slow it was heartbreaking.

Not long ago, they began commuter train service from downtown to the northern outskirts, a place called Cuautitlán Izcallí that is actually situated in Mexico State but considered part of the urban sprawl of Mexico City. Although it's a ride of only a little more than twenty miles, traffic tends to be so bad that it can easily take you two hours or more to get there or back in a car. I had only been to Cuautitlán once, a few years ago, and the ride home in a taxi was so excruciatingly slow it was heartbreaking.

The downtown port is what used to be the Buenavista train station, where people took long-distance passenger trains. It had been defunct for close to twenty years. Mexico still has a lot of cargo rail service but no longer takes passengers anywhere, except for the privately run trains that go to the Copper Canyon in Chihuahua and from Guadalajara to the tequila factories.

The new service has definitely been built for people who live in Mexico State but work in Mexico City. At the downtown station there are several machines like the one above, which buff your shoes free of charge.

The train is something of a phenomenon. I wonder how many like it there are in the developing world. It's sleek, comfortably functional (there are few seats, but lots of room for standees, and even compartments to store packages overhead). Above all it's fast (I made it through the seven stops to Cuautitlán in a half hour) and cheap (from one end of the line to the other, service costs a mere thirteen pesos).

Yet the message the vehicle conveys (comfort, function, speed, sleek design) has little to do with the riders it transports. Out of the windows you see the misery that is Mexico State, the extended shantytowns on the hills, the corrugated tin roofs, the cinder blocks, the plastic sheets in place of windows, the steam billowing from a factory smokestack.

I had hoped to have a coffee in Cuautitlán when I got out at the other end, but there wasn't any to be had. Just more tin-roof shacks, empty lots covered in weeds, the railroad tracks. I got back on the train and returned, once again reflecting on the vast differences between my life and those of so many others in the city.